Use templates for better Git commit messages

Commit messages are important. They are a means of communication with yourself and your team throughout the life of your codebase (remember that team members are likely to come and go over time.) In fact, given that they live alongside the code, they’ll probably be the best source of documentation that you have about the evolution of your codebase. Commit messages are important!

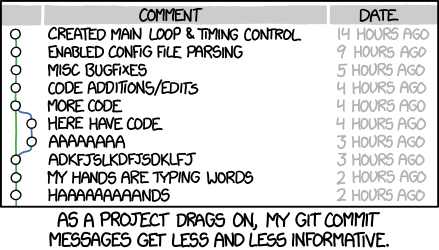

Bad commit messages

Before we consider what good commit messages look like, how about bad ones?

“Git Commit” by XKCD licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License

César H. Vortmann observes 1 that bad commit messages very often fall into two categories:

-

Uninformative commit messages

bug fixescopy editMajor refactor of all the stuffs

-

Look-elsewhere commit messages

fixes #123[JIRA-123] update user registrationFix ‘boo’ bug (ask Geoff for details)

I’d argue that look-elsewhere messages are actually a subset of

uninformative messages - they are not informative themselves, but rely

on a separate source of information which may or may not be available at

time of reading. I’m not suggesting that you shouldn’t include a

reference to an issue tracker or other work management system, just that

this is not enough on its own. That said, it should be obvious that

ask Person X is never acceptable!

Good commit messages

A good commit message should tell the reader, why the change was necessary, how the change addresses that need, and any side-effects the change will introduce2,3.

The language and syntax of commit messages are also important, they should make sense and be easy to read. That means simple sentences with basic punctuation. As a minimum you should use capital letters and full stops, with blank lines to separate paragraphs (yes, it should be a common occurrence for commit messages to contain multiple paragraphs!)

I also like to make sparing use of some basic Markdown sugar, particularly backticks for short code snippets (e.g. class, method or function names), and hyphens for creating bullet lists. These don’t reduce readability in an ASCII context, and really come into their own when reviewing code or pull-requests in GitHub. You should though, save your emojis for Slack, and your ascii art for application boot banners!

___ _ __ _ _ __

/ _ \___ ___ ( ) /_ __ _____ ___ ___ ____ ____(_|_) ___ _____/ /_

/ // / _ \/ _ \|/ __/ / // (_-</ -_) / _ `(_-</ __/ / / / _ `/ __/ __/

/____/\___/_//_/ \__/ \_,_/___/\__/ \_,_/___/\__/_/_/ \_,_/_/ \__/

_ _ __

(_)__ _______ __ _ __ _ (_) /_ __ _ ___ ___ ___ ___ ____ ____ ___

/ / _ \ / __/ _ \/ ' \/ ' \/ / __/ / ' \/ -_|_-<(_-</ _ `/ _ `/ -_|_-<

/_/_//_/ \__/\___/_/_/_/_/_/_/_/\__/ /_/_/_/\__/___/___/\_,_/\_, /\__/___/

/___/

Created using Text to ASCII Art Generator

The seven rules

In a terrific blog post, Chris Beams lays out seven simple rules for a good Git commit message, and gives compelling justification for each4. I won’t re-hash the reasoning behind the rules here, but will simply quote them:

- Separate subject from body with a blank line

- Limit the subject line to 50 characters

- Capitalize the first letter of the subject line

- Do not end the subject line with a period

- Use the imperative mood in the subject line

- Wrap the body at 72 characters

- Use the body to explain what and why vs. how

I tend to use a single line view of the Git commit history (like the one

you get in IntelliJ or from the command git log --oneline --graph)

quite a lot, so for me the rules about the subject line are the really

important ones.

Seven simple rules; we could all remember to follow those, right? Oh, OK we can set ourselves a timely reminder with some templating.

Templating

Tim Pope originally set out this template 10 years ago 5. He also gave additional compelling reasons to follow Rule 6.

Capitalized, short (50 chars or less) summary

More detailed explanatory text, if necessary. Wrap it to about 72

characters or so. In some contexts, the first line is treated as the

subject of an email and the rest of the text as the body. The blank

line separating the summary from the body is critical (unless you omit

the body entirely); tools like rebase can get confused if you run the

two together.

Write your commit message in the imperative: “Fix bug” and not “Fixed bug”

or “Fixes bug.” This convention matches up with commit messages generated

by commands like git merge and git revert.

Further paragraphs come after blank lines.

- Bullet points are okay, too

- Typically a hyphen or asterisk is used for the bullet, followed by a

single space, with blank lines in between, but conventions vary here

- Use a hanging indent

If you plan to introduce a template (and especially if you intend to mandate one), you should have a discussion with your team about any other elements that they feel they need in order to get the most from the git commit history.

For example on our team, people felt strongly that having the issue or story number in the summary line helped when carrying out code reviews on large codebases. We also followed the advice of Caleb Thompson 3 and included a full link to the issue tracker in order to disambiguate—in the 18 months that our team has been together, we’ve already used three different tools for tracking work!

Another thing that our team felt strongly about was that we needed to

include who worked on the commit, so that questions could be directed

appropriately during subsequent code review. Normally I wouldn’t

advocate adding anything to the message that would already be

automatically included in the commit metadata (e.g. author name,

list of affected files). However, in this case the available alternative

(using the command line --author option or the Author field in

IntelliJ’s commit dialogue to add the second member of the developer

pair) was considered too clumsy, and still wouldn’t work for

mob programming.

The recent release of support for Co-authored-by trailers in

GitHub

and GitHub Enterprise

probably offers a better solution, so it’s probably time for a review of

our current template. When we get round to having this review, I’ll be

suggesting that our template takes the form:

9999 Add/Change/Refactor feature up to 50 char >|

https://tracker.example.com/issues/9999

Why this feature or fix was necessary/desirable. Be sure to hard-wrap

at 72 characters!

Optional notes on why the feature or behaviour was implemented in the

way it was, and side-effects or other consequences.

Co-authored-by: Person Name <person.name@example.com>

OK, so now you’ve got your template, you really want it to appear in the editor automatically when you’re committing your changes. Luckily this is pretty simple:

- Open the file

~/.gitmessage, write your template and save. - Open the file

~/.gitconfigand add a section:[commit] template = ~/.gitmessage

And that’s it! Next time you run git commit from the command line,

your editor of choice should pop up pre-populated with your template.

JetBrains commit dialogue integration

- Install plugin ‘Commit Message Template’ v1.0.3

- Preferences > Tools > Commit Message Template

- Write your template in the ‘Set Template’ text area

-

OPTIONAL: Commit your commit message template

git add -f CommitMessageTemplateConfig.xml - To load the template into the commit dialogue, click the icon

More complicated workflows

Feature branches

Some developers’ workflow consists of very frequent, very small commits

in a feature branch, which is merged into the trunk (commonly the

master branch in git) using the --squash option when the feature is

finished. In this case it might not make sense to include the story link

and the motivation for the work in every commit message, especially when

you consider that the bodies of the squashed messages are lost when

they’re merged.

That said, the all important ‘subject’ line is retained

by default when you run git merge --squash my-feature-branch, so I

think it’s still worth putting in the effort to write these well. That

way, when you do come to write your message for that final merge commit,

you’ll be presented with a nice neat list of all the small steps that

you made on the way to your complete feature.

This final merge commit is also the place to include the motivation for the new feature, a link to the issue or user story that describes the desired feature and any other information that the development team has agreed should be included in commit messages. In short this is the commit that should conform to the team template.

Pull requests

Some teams and software projects, and especially large well established open-source projects such as the Linux kernel6, will have established policies on how they expect you to make pull requests. In the absence of a clearly communicated process, I’d advise following the seven rules. The aims of a pull request message are the same as they should be for a commit message, namely to convey:

- Why the change was necessary

- What solution you chose (and why you discounted any alternatives)

- Any side effects your change has

I can’t word this better than the Linux Kernel Maintainer Handbook page on creating pull requests quoting Linus Torvalds6:

the important part [of a pull request] is the message. I want to understand what I’m pulling, and why I should pull it. I also want to use that message as the message for the merge, so it should not just make sense to me, but make sense as a historical record too.

If your pull requests fixes a bug or adds a feature described in an issue tracker somewhere, you should definitely include a link to that too.

References

- What makes a good commit message?—César H. Vortmann

- On commit messages - Peter Hutterer

- 5 Useful Tips For A Better Commit Message—Caleb Thompson

- How to Write a Git Commit Message—Chris Beams

- A Note About Git Commit Messages—Tim Pope

- Kernel Maintainer Handbook » Creating Pull Requests

- The (written) unwritten guide to pull requests

Enjoyed that? Read some other posts.