Let's Encrypt at Scale

Enabling HTTPS on 3,000+ websites is a bit of a pain. But as we are now in the age of increasing online privacy, we had to knuckle down and find a way to do it. We provide a platform for trade dealers to upload and advertise their stock online. As an extension of this, we offer a product that allows customers to host a private website using this stock, under their own domain. We wanted to provide HTTPS support to all of these websites.

Update (Sep 11, 2018): Some discussion has come up around this post, and have (rightly) pointed out that there are solutions that will provide this facility. Whilst we did do some rigorous searching to try to find more out of the box solutions (both for requesting certs and secure storage of the associated private keys), at design time we couldn’t really find a solution which seemed to fit the bill. Turns out we were rigorously searching for all the wrong things. Suggested solutions such as Cloudflare, Caddy, and Openresty can provide this, and I would strongly recommend investigating these as your first port of call.

Caddy was actually solution that we encountered late into development, but decided against migrating to it as we were unsure of the time that would be taken in adapting our secure key storage solution to work with it (if somebody could additionally suggest a solution for secure mass key storage, I will add that in here too!).

(Thanks to Hacker News commenters “simplyinfinity” and “nodesocket”, and Reddit user “procipher” for the suggestions)

Update (Sep 12, 2018): The question came up of donating to Let’s Encrypt, to say thanks and support them in their work. In response to the question, Auto Trader wants to issue the following statement:

Auto Trader’s Make a Difference strategy extends to supporting the wider technology, automotive, advertising and creative industries. We believe that the important work the Internet Security Research Group are doing with Let’s Encrypt is vital to the technical industry, and that they have delivered a real improvement to our community.

For that reason, as part of this project, we decided to support Let’s Encrypt with a donation to recognise their work and the value that we have received from it. We would encourage others to donate too, particularly organisations who rely on their services to provide certificates.

The first thing to worry about is cost. The simplest solution would have meant purchasing certificates for each domain, and then adding them to our load balancer alongside our existing Auto Trader certificates. This would either mean us absorbing this particularly hefty cost, or otherwise asking customers for additional money, which is of course what nobody wants to hear. Fortunately, a service called Let’s Encrypt came to our rescue. This non-profit service allows us to obtain HTTPS certificates at no cost. The cost involved in requesting a certificate usually goes to ensuring that nobody dodgy is trying to claim it for nefarious reasons, so Let’s Encrypt had to find an alternative way of handling this.

Let’s Encrypt uses an automated system that verifies you “own” the domain, checking that you have control of it. Unlike regular certificates which can last for years, Let’s Encrypt makes it their policy to expire them regularly, forcing you to redo the verification process each time. Whilst this solved the problem of expensive manual verification methods, this did mean that we had to have something in place that handled this process elegantly.

Initially, we asked, “does somebody already offer such a thing”. After some research, nothing that would fit our needs turned up (though this might not be the case anymore). So we had to roll our own solution.

This blog covers our experience of developing a solution to this problem. We based this solution on Etsy’s own solution to the same problem, which they made an excellent blog post about. I strongly recommend reading this first; I’m going to avoid retreading the same steps too much.

Prototyping & Design

First of all, we wanted to better understand and prove out technically that is involved in the Let’s Encrypt certificate request process. This is a simple enough mix of reading and using Certbot (Let’s Encrypt’s official client) alongside NGINX to build up a basic demonstration. We got this working and issuing self-signed certificates in no time.

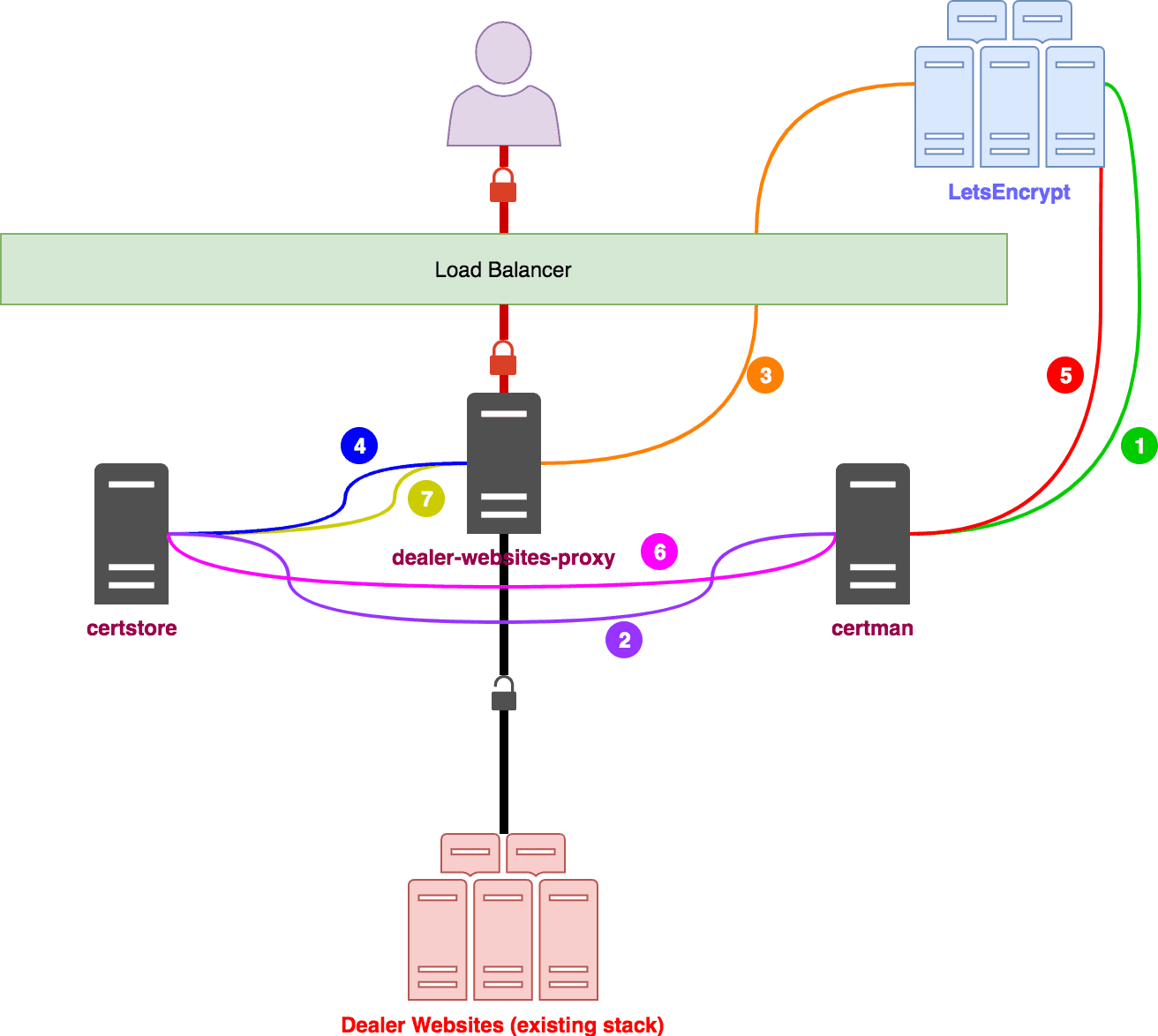

Now we needed to move towards making something more realistic, and make a rough prototype of an actual solution. Using Spring Boot and the acme4j library, we had something knocked together quite quickly which demonstrated that we weren’t wasting our time down the wrong rabbit hole. Then we agreed on a final design consisting of 3 services:

- “certman” - The service that handles all negotiation with Let’s Encrypt.

- “certstore” - A dumb API layer on top of storage to hold both active “challenges” and public/private key data.

- “dealer-websites-proxy” - The proxy layer that will serve the certificates and answer Let’s Encrypt “challenges”.

Implementation

Now we were free to throw away our prototypes and get cracking on what would be the actual implementation. As of

writing, it looks something like this:

Following this, we can go through the process our stack uses to grab a certificate step by step:

- Tell Let’s Encrypt what domains we need, and accept a “challenge” to prove that we own them.

- Take the details of the challenge that we were issued and store them in “certstore”.

- Let’s Encrypt will now attempt to make a HTTP request to the requested domain on a specific path.

- Our proxy will notice that the request is a challenge request, and forward it onto a “certstore” endpoint, which will respond with the challenge data Let’s Encrypt told us to put there.

- Once all of the domains have been verified, we can then negotiate the actual certificate from Let’s Encrypt.

- Once we have a certificate, we can encrypt and push the certificate and associated data into “certstore”.

- Our proxy will notice that new certificates have appeared, and will proceed to download and decrypt them before including them in its set of live certificates.

The stack was made to require as little maintenance as possible; renewals happened when needed, and were retried after a reasonable delay when they fail. Failing to renew before the certificate runs out will trigger an alert for potential manual intervention. Requests to Let’s Encrypt are paced out client-side so that even if we renew/create many new certificate requests at the same time, we will not exceed Let’s Encrypt’s rate limits, so it wouldn’t suddenly stop talking to us (Let’s Encrypt do offer to lift these limits for much heavier workloads, but this wasn’t necessary for us).

Going Live

Going live was the tough part. Suddenly provisioning and serving certificates for several thousand websites was something we wanted to avoid (we didn’t want any downtime). Ultimately, we decided against just throwing it out and putting our fingers in our ears and instead came up with a plan:

- Get the service into Live without sending it any traffic, and make sure it is behaving.

- Start monitoring! We have plenty of logs and metrics available to us so that we can keep an eye on the health of the system in real time.

- Sneak in the proxy service; we want all traffic to start going through the proxy in its present unencrypted state at first. This allows us to minimise change and more easily handle issues. Working closely with our Operations team, we migrated traffic a bit at a time, ready to roll back should anything fall over.

- Get a certificate and enable HTTPS for one of our live test sites; we wanted to test actually setting up a real site with a certificate. This would be risky to do with a customer at this point, but fortunately, we have several live test sites for this. We set up this site in “certman”, and made sure that we could now access it over HTTPS. You don’t realise how pretty Chrome’s green “https” is until you get to this point.

- Onboard all of our test sites, monitoring increases in load.

- Get our first customer onto the system; now we can start to see our stack perform under realistic load.

- Onboard remaining customers in batches, keeping an eye on load. Due to quantity, a throwaway script was prepared to do this for us.

- Cleanup. Now we can throw away legacy network configuration that is no longer relevant thanks to our updated proxy mechanism.

This went fine. Absolutely fine. Well, that was until we encountered the obviously-going-to-happen major issue…

Decryption isn’t Easy

This section discusses “cryptography”, a method of changing data so that it may be securely transmitted/stored (using encryption, for example). I don’t go too technical here, but some knowledge of the basics will be useful, so I will include some useful links in the further reading section if you want to brush up on your knowledge.

As mentioned, we relied on a similar mechanism to Etsy to make sure that, should somebody manage to get into our network, at the very least they have little opportunity to be able to compromise our customer’s HTTPS certificates. Our key pairs are kept safe by making sure that:

- They are encrypted in transit.

- They are encrypted in storage.

- They can only be decrypted at point of use. We ensure this using hybrid cryptography: AES can be used for encrypting content, RSA can be used to asymmetrically encrypt the AES key.

We soon found that this was really not very performant. Our deployment tech started to disagree with our proxy as it did not appreciate our app sitting around for 5-10 minutes whilst it loaded certificates. Things came to a head when it reached a point where our code wasn’t considered releasable by the deployment system. This isn’t a fun situation to be in.

After fiddling around with attempted concurrency improvements and getting nowhere, we looked to changing the encryption mechanism itself to try and make it run a bit quicker. Due to every instance needing run this decryption process, it is not a problem we could throw more machines at, and we were hesitant to make this a special case with more virtual CPU access if we could help it. At first we looked at ECC cryptography as an alternative to RSA. ECC keys of equivalent strength to RSA keys are smaller, putting less pressure on the system in most scenarios. We soon found to our dismay that ECC does not have an encryption scheme equivalent to RSA, instead being used as an alternative only in key negotiation.

Fortunately, an even better solution came along: ECIES. This is a hybrid encryption standard that makes use of ECC key negotiation. The icing on the cake is that as this is a hybrid encryption mechanism as standard, implementing libraries do both the symmetric and asymmetric encryption under the hood. This means people like this blog’s author won’t make a pig’s ear of it. After running some tests which showed some positive speed improvements we went forward with integrating it.

In an ideal scenario, we would have thrown it in and been happy with our new super-fast encryption. Unfortunately, our system was live, securing connections already. We had to migrate existing customers, and so had to support both encryption mechanisms at the same time; new certificates provisioned would use ECIES, whilst existing certificates would use the legacy RSA/AES encryption scheme.

Due to us being super secure in our approach to storage, we couldn’t easily reread and re-encrypt our data either, so we took an alternative approach. We wanted to spread out our certificate requests anyway, as we had provisioned them in bursts. To avoid renewals also happening in bursts, we set it up so that the certificates would request renewal sooner, and over a spread out period. New certificates were encrypted using the new scheme. Two birds, one stone.

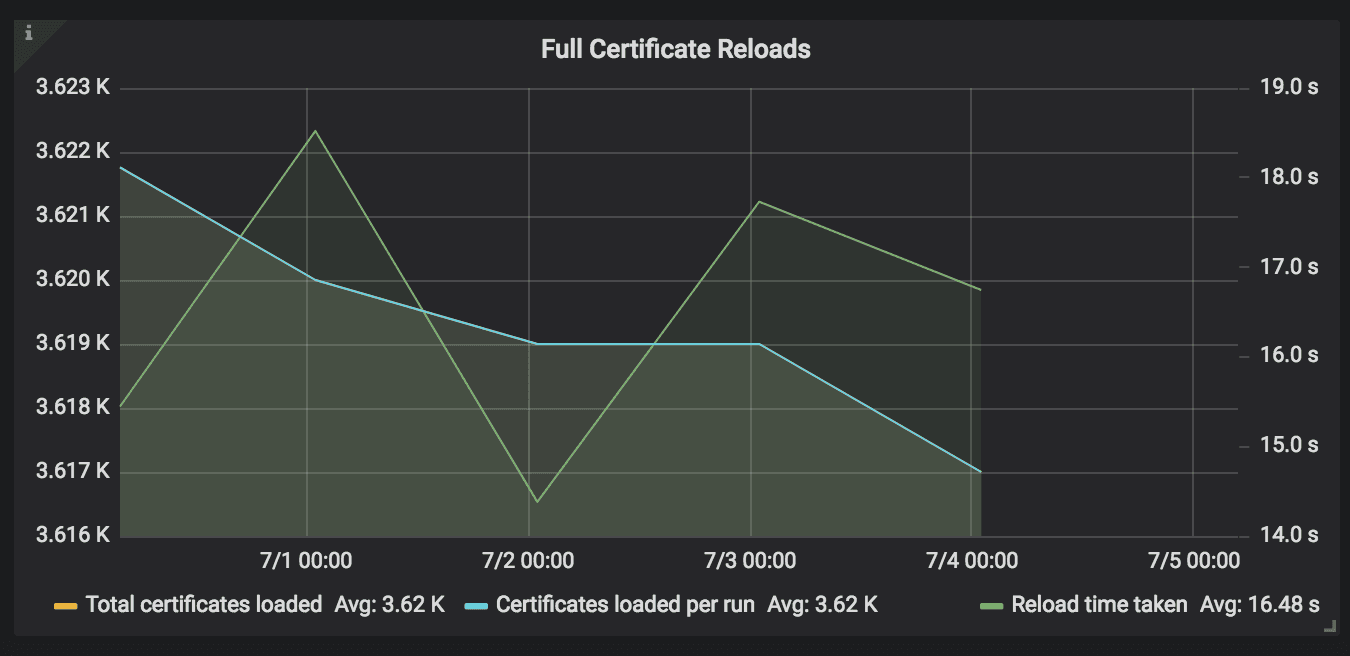

The results were actually significantly better than expected. Releases that took 5-10 minutes dropped into the seconds, and the application code became simpler to boot (once we made a pass to remove the legacy support). Panic over.

Current timings… seeing this still brings tears to my eyes

Current timings… seeing this still brings tears to my eyes

In Retrospect

This was a great project; the opportunity to work with layers you don’t often touch offers constant challenges and opportunities to learn. And you really miss StackOverflow when working in areas where not too many tread.

I think something that we could have done better was to contribute additional features to the acme4j library. There were a few workarounds that we ended up writing that would have been easier to add to the library directly, and potentially could have been useful for others. Something to bear in mind when working with “inaccessible” code; if it is open source, it isn’t “inaccessible” at all!

As mentioned before, as networks evolve and HTTPS becomes even more ubiquitous, we fully expect out of the box solutions to pop up that solve this problem better than we did. And we will be happy when this replaces our stack. It isn’t that we think our work is awful (it has managed to purr away in the background just fine over the past months), but there is something to be said for software whose sole focus is providing this technology out of the box. Remember that your code is cattle, not a pet. Attachment makes separation very difficult.

Further Reading

Let’s Encrypt

- Let’s Encrypt - How It Works by Let’s Encrypt

- How Etsy Manages HTTPS and SSL Certificates for Custom Domains on Pattern by Andy Yaco-Mink and Omar

Cryptography

- Asymmetric Encryption - Simply Explained by Xavier Decuyper

- ECC 101: What is ECC and why would I want to use it? by Julie Olenski

- Cryptography 101: How a Symmetric Key Exchange Works (Basically) by Vanessa Pyne

HTTPS

- How does HTTPS actually work? by Robert Heaton

That’s all from me, time for me to get back to being a busy bee.

Enjoyed that? Read some other posts.