How we secured our payment pages using a Content Security Policy

In the Private & Home Trader Advertising squad we take payments for advertisements through our in-journey payment pages. Previously our payments were handled by a re-direct to a third party payment provider. When we decided to bring the payment pages into our journey, using Stripe elements (Stripe components embedded within our pages), it was vital that we secured our payment pages to eliminate any risk from malicious scripts or injection attacks. Here is how we did it.

Why was there a security risk?

At Auto Trader we love to learn from data. We do this by tracking user actions as they progress around our site. Doing this allows us to tailor a user’s experience to create the best user experience possible. A lot of this tracking is done using third party libraries that load JavaScript via a tag manager. Nothing wrong with that right? Unfortunately, any source code that is not within our control should be viewed as vulnerable. Indeed, according to The Register, the recent breach of British Airways payment data was rumoured to be caused by a compromised third party JavaScript library. Therefore, in the context of our payment pages, we decided to view any third party code as potentially rogue!

Other risks

As well as compromised third party libraries, we also looked at how malicious parties could look to directly inject rogue code into our payment pages through other methods. We identified that, as well as JavaScript, there were other potential risks, including:

- Inline styling

- Loading of external fonts

- Loading of images

- Allowing loading of frames (such as for the Stripe components)

- Front-end calls to back-end APIs

What is a CSP?

CSP stands for Content Security Policy. It is essentially a security policy that instructs a browser where it can (and therefore implicitly cannot) load content from.

How does a CSP increase security?

By instructing the browser that it is only allowed to load content from certain sources it prevents malicious code from executing to capture data and then forward it onto unwanted sources. Let us imagine for a minute that a third party library has been compromised by some malicious JavaScript, or some JavaScript has been injected directly into our payment page. This malicious script could scrape payment data and forward it on to a URL to capture the data for later fraudulent use. By using a robust CSP we can prevent the above scenario in three different ways:

- Prevent loading of third party scripts

- Prevent injection of JavaScript directly into the page

- Prevent sending of any scraped data to a URL

A CSP can prevent all of these actions from occurring with some simple directive.

What does a CSP look like?

A CSP is returned in a HTTP Response Header and appears as follows:

default-src https://www.autotrader.co.uk; style-src 'self';

font-src 'self' https://c.atcdn.co.uk https://fonts.gstatic.com;

img-src 'self' https://i.atcdn.co.uk https://www.gstatic.com;

frame-src https://js.stripe.com https://www.google.com;

connect-src 'self' https://www.autotrader.co.uk;

script-src 'self' https://js.stripe.com https://www.google.com/recaptcha/api.js https://www.gstatic.com/recaptcha/api2/;

report-uri https://autotrader.report-uri.com/r/t/csp/reportOnly

The intention of this article is to focus on our implementation, so we won’t go into the full details of each directive within a CSP. However, from our current directive you can see that we only allow any content to be loaded from either ourselves, Stripe, or Google (used for analytics and reCAPTCHA functionality). For further information on the directives themselves see the CSP Reference.

Restructuring our code

We were fairly lucky. We only had to worry about our payment pages (for now at least), and the changes that we needed to make were fairly limited. However, we had to be adamant we had not broken anything prior to releasing to production—this is covered more in the reporting section.

Tag Management Code

We made an early decision to remove all tag management code from our payment pages. As we did not have it on our previous external payment pages (given that they were outside of our control), we decided we did not need all of our tags to load on our new internal payment pages. This was an easy decision to make and just required implementation of an easy way to switch off this functionality.

JavaScript

Our CSP prevents loading of any JavaScript other than from self, Stripe or Google (gstatic is Google reCAPTCHA code). The self directive essentially allows loading of content from the same origin i.e. JavaScript code within our app. It does not allow any inline JavaScript to be executed (to prevent injection of code). The effect of this was that any inline JavaScript had to be moved from within our pages and into their own script files.

<script>

!function (global) {

if (!global.tmpl) {

global.tmpl = {};

}

...

}

</script>

The above example would need splitting into two components: a script file containing the JavaScript code, and then the inline call needed replacing with a reference to this script like this:

<script src="../../js/lightbox.js"></script>

As our CSP allows a script-src of self this works perfectly well.

Events

JavaScript events are used to perform some form of action when an event fires, for example clicking of a button. Our CSP now blocks inline JavaScript so this needed changing. Although we had a few cases of these, they were simple to address by moving the events to a bound event listener.

<button onclick="document.cookie='bucket=; path=/'; document.location.reload();">

Desktop

</button>

The above example was fixed by adding an id to the button and replacing the onclick code from the button with an event listener binding in a JavaScript file like this:

<button id="switchToDesktopBtn">Desktop</button>

//External JS file

switchToDesktopBtn.addEventListener("click", function()

{

document.cookie='bucket=; path=/';

document.location.reload();

});

Styling

As with inline JavaScript, inline CSS is also vulnerable to malicious attacks. When I first started the work to secure our payment pages I did not envisage that inline CSS would be vulnerable in the same way as JavaScript but it is. See the OWASP site for further information on this. Inline CSS was fairly simple to replace, replacing inline styles with a reference to a class where the style can be specified.

Here we are hiding an element using inline CSS:

style="display:none"

We resolved this by adding a hidden CSS class:

class="hidden"

The hidden CSS class implements the correct style for hiding the element:

.hidden {

display: none;

}

Images/Fonts

We have a couple of CDNs (Content Delivery/Distribution Networks) that we use within Auto Trader—one for fonts and one for images. There was no specific code that needed changing for this, we just had to ensure that our CSP allowed the browser to talk to our CDNs to pull down the required content. As with our other CSP directives we do not allow any inline fonts or images to be loaded.

Frames

Again—as with the CDN—we just needed to ensure that our CSP allowed both Google and Stripe to load content within an iFrame. For Stripe this is their secure payment elements and for Google this is the reCAPTCHA code.

Validation

The ever present danger of implementing our CSP was that, no matter how much validation we did in a preprod environment, it could still cause problems in production and therefore prevent users from paying for their adverts. This was our worse-case scenario. In order to mitigate these concerns, CSP helpfully provides for a Content-Security-Policy-Report-Only directive. Instead of actively blocking content, this directive will just report on any content that violates the directives while still actually loading the content. The report-uri directive allows definition of a URI to send this data to.

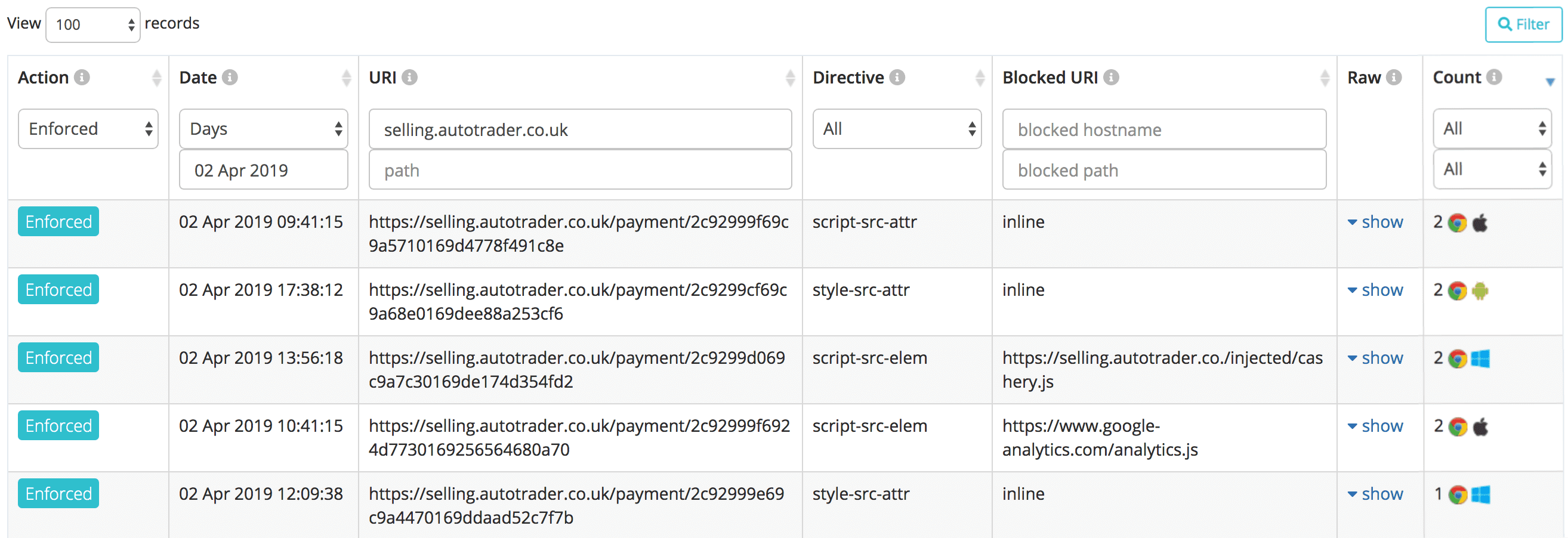

Rather than writing our own endpoint we make use of the brilliant report-uri site that—amongst other services—provides a facility for sending all of your CSP violation report data segmented by various criteria as seen below:

We ran with our CSP in report-only mode for several weeks, gradually tweaking our policy until we were happy with the violations that were being reported. At that point we were ready to put it live.

Limitations

There is one big limitation with having a CSP. As browser plugins have absolute control over your browser, they are able to re-write the response header that contains the CSP. You really should be aware of the power you are giving to any browser extensions when you install them, but unfortunately there is nothing that we can do to protect against this without severely hampering our user experience. I do not use any browser plugins for this exact reason!

Having said this, there are some browser plugins that are especially useful, particularly when it comes to accessibility. A lot of these plugins work by manipulating data on the page, via either inline JavaScript or inline CSS. Whilst we regret that these will no longer work and could hamper the experience for some users, we decided that this was secondary to the security of our user data.

Further steps

We will soon be refining our CSP further as we have identified we no longer need the Google reCAPTCHA service on this page. We will continually be looking to ensure that our payment page CSP is as secure as it can be. We have tests in place to ensure that our CSP is not violated by new code, nor accidentally changed. Our future plans also include rolling out CSPs across our entire site to further enhance our security.

Sub-Resource Integrity

As we are still pulling in some third party libraries (Stripe and Google), we will be looking to implement Sub-Resource Integrity checking. This is used in order to validate that the third party library code has not changed from what was expected. This adds an additional security layer by ensuring that in the event the third party library has been compromised, it will not load, and therefore cannot be used maliciously.

Summary

We have shown how we have used a robust CSP to ensure that our payment pages are as secure as they can be whilst maintaining a good experience for our users. I’ve also found this a good learning exercise for considering security implications when developing public facing websites, especially those that process payment data!

Enjoyed that? Read some other posts.