How we (almost) completed a natural language recipe recommendation engine using Twitter in a 24-hour hackathon

On 28th October we four Java developers attended HAC100’s Hack Manchester event. A 24-hour hackathon of coding, coffee and chaos (25 hours really as the clocks went back). We were one of three Auto Trader teams out of about 50 in total. Our team took on the dunnhumby challenge, “to use technology to enhance the retail experience for a customer in the home or in store.” By the end, we had built a personalised recipe recommendation engine with a natural language based Twitter interface.

Hack Manchester

Hack Manchester is a hackathon organised by HAC100 who also run events focused on younger age groups (as young as eight). The event is well run and aims to balance chaos with some structure. It has challenges and prizes from sponsors to provide some inspiration and motivation. Auto Trader has taken part since 2014 as sponsors and competitors.

Team Ballmer Peaky Blinders

Our team was made up of four developers who usually work on consumer-focused products at Auto Trader: Andy May, Leon Pelech, Phillip Taylor and Simon Dudley.

Ballmer Peaky Blinders was the name we settled on. It’s a suitably bad geeky pun on The Ballmer Peak and everyone’s favourite Brummy gangsters.

It seemed appropriate since Auto Trader was sponsoring the bar at the event and HAC100 had a joke about reaching the Ballmer Peak in the pre-hack literature. At least one team member was from Birmingham but other than that we have no connection with the post-war criminal underworld.

In retrospect, it was a pain to type and spell correctly every time we wanted to test stuff!

Idea

At a high level, we wanted to tackle the challenge to “enhance the retail experience” by solving the problem of what to make for dinner. We’ve all stood in the kitchen after a busy day with some cabbage, a packet of spaghetti, a tin of kidney beans and zero inspiration. Our MVP was to create a service which could make suggestions about what to cook based on some specified ingredient.

The Plan

Although a lot of the hack was made up as we went along, we first formulated a bit of a plan. There were a number of aspects we needed to get working together.

- Recipes: We knew we needed a source of recipes that we could search based on ingredients.

- Shopping History: We needed to be able to do personalised, data-driven recipe recommendations based on user shopping history.

- Recommendation Engine: Something had to bring together the shopping history and the recipes; we knew technology already existed to help us do this.

- User Interface: We needed a simple way to specify the ingredients and receive a recommended recipe.

- We wanted to use Kotlin as the programming language because it looks great, but none of us had had an excuse to use it before.

The Reality

As with any hack, the plan is just a starting point. Below we’ve described our journey and the decisions we made.

Recipes

We had put thought into where we would get recipe data from in advance. At first, we had hoped that there might be a data-dump of recipes that some kind person had released which we could import and analyse.

Much Googling later, the best data set we could find was on Github. This data set was exactly what we wanted… except for the slight drawback of being in Norwegian.

Instead, we looked for an open API which is when we found Yummly. Yummly had a well-documented API which we would need to write a client to interact with. They even had a “Hackathon Plan” that you could register for to get free access for a limited time. We signed up the day before the hack and had the account approved only hours before the hack began.

We started writing our Kotlin data model classes for a Yummly client to search for recipes. Even though Kotlin makes writing simple data classes much less painful than Java, this was still a fair bit of typing and we had a deadline to hit. It didn’t take us long to find this promising repo created by Mads Kalør. There were no binary artifacts to depend on but we could copy the source into our project!

After a quick test, we could now search for recipes!

Shopping data

The challenge suggested using an open source data set from Instacart which we would need to download, parse and analyse. This was a significant task due to the size of the data set — see below for more details. Their data allowed us to mine a single user’s past orders by joining the order table with the product table. This would allow a naive recommendation engine based on that user’s past orders. However, with a little effort, we could use all of the users’ collective data to make richer recommendations.

Richer recommendations

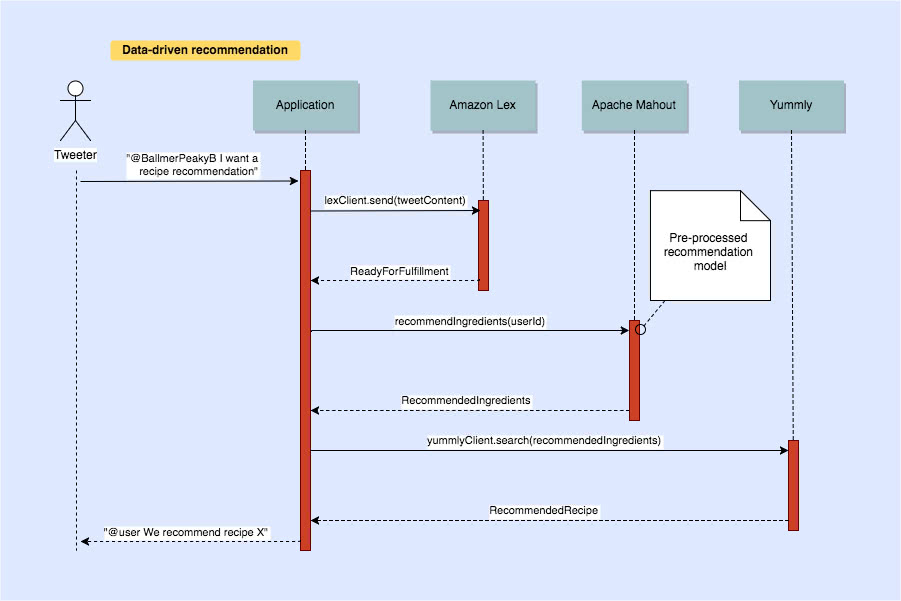

To use all of the shopping data to provide recommended ingredients for users we utilised Apache Mahout. This required a bit more pre-processing of the data before letting Mahout build a recommendation model. By supplying a user ID, Mahout finds other similar users and then returns a collection of recommended product IDs. We then map these products to Yummly ingredients.

Twitter as a user interface

This is what happens when you get four backend developers to design a frontend… they don’t. Very early on we decided that time was too short to learn CSS and that we could just use Twitter as our user interface. With a couple of libraries to listen to and send tweets we could respond to mentions, admittedly not with the most user-friendly message, but a response is a response.

@SiLaDu - Bad user, no recipe for you: 21:38:54.470

— BallmerPeakyBlinders (@BallmerPeakyB) 28 October 2017

Next, we needed to hook it up to our Yummly client so we could start sending recipe suggestions. In the first draft, the tweet text (excluding our @BallmerPeakyB mention) was fed into Yummly as a search query to get a recipe suggestion. Extracting the recipe name and a link to the recipe allowed us to send a recipe suggestion reply.

11 hours into the hack we had a working MVP:

We recommend Spicy Tomato Butter https://t.co/xlrtoHCm11 01:14:06.658

— BallmerPeakyBlinders (@BallmerPeakyB) 29 October 2017

Yummly recommendations include image links and we wanted to include one of these images as part of the recipe recommendation to the user. It looked something like this:

We recommend Butternut Squash and Bacon Penne https://t.co/PJHV1pQiF7 pic.twitter.com/K5mJigf9c9

— BallmerPeakyBlinders (@BallmerPeakyB) 29 October 2017

Improving the experience

The bot was working but not the most pleasant user experience. Yummly lets you build quite complicated searches for recipes but building the search criteria required working out what a user wanted from only the contents of their tweet.

To extract the meaning from a tweet we would need to do some natural language processing. NLP isn’t the simplest field and none of us had any experience, so some research was needed.

Natural language processing

We were halfway through the hack at this point so whatever approach we chose had to be one that could be picked up by some sleep-deprived devs in a few hours. The first decision was whether to build our own NLP service or use a SaaS one. There are a lot of tools out there to build NLP services but many of them are machine learning based and required training data. Figuring out which library to use and how to train and debug was too much to bite off at 2 am so we looked for SaaS offerings.

Machine Learning as-a-service is becoming an important product for cloud providers so there are some options out there, but we didn’t have much time so a snap decision was in order. Amazon Lex looked the simplest and the getting started documentation seemed decent so we decided to use it. See below for more about our findings.

Final technology stack

- Kotlin—”Java without the boilerplate” - Ideal for prototyping/hacking for a tight deadline.

- Apache Mahout—Machine Learning user recommendation engine (and much more).

- Amazon Lex—The technology underpinning the Amazon Echo Alexa conversation engine.

- Hosebird Client—Twitter’s client library to consume their streaming API.

- Twitter4J—Twitter API client for Java (interoperable with Kotlin).

- Yummly Recipe API—An API for finding recipes based on ingredients. They even have a “Hackathon Plan” for limited free usage.

The result

We ended up with two main features, or two ways to retrieve a recipe recommendation:

1) A personalised recommendation based on user shopping history.

2) A natural language conversation gathering details about the desired cuisine and ingredients.

The first feature is shown in the video we submitted as part of our entry. Yes, it’s terrible because we were coding up to the last ten minutes. It transpired that most teams spent significantly longer on their video so our submission came woefully short!

What you just saw was our app recommending a recipe based on a known user’s previous shopping history.

Below is a sequence diagram showing simplified system interactions for the personalised recommendation feature.

Next up is a video of a natural language conversation resulting in a recipe recommendation based on the ingredients given.

Disclaimer: This was recorded after the hack following a few minor bug fixes (related to maintaining the state of the conversation) which meant we couldn’t include this feature in the original submission.

Next time we’ll hire a video editor :)

If you care to look at the code, it’s here: https://github.com/siladu/recipe-recommender-hack

Summary

Hackathons like this are an amazing chance to really get out of your comfort zone. With the results ceremony at the end, it lasted the whole weekend giving you a chance to get really stuck into a problem while being surrounded by some great minds who are always willing to help.

Some people treat them as a networking opportunity. However, we had our heads down (or whole body down, wrapped up in a sleeping bag under the table, in Phil’s case!) the whole time because we were so determined to get it all working.

It’s always surprising what curious and determined people can achieve in such a short space of time, so seeing the final showcase of everyone’s work is a humbling experience. It’s hard to describe the incredible buzz you get from hours of individuals hard work finally coming together in a mad rush at the end.

Technologies used and their challenges

Yummly

The API itself is very usable; to find a recipe including garlic the query is:

http://api.yummly.com/v1/api/recipes?_app_id=<OUR_ID>&_app_key=<OUR_APP_KEY>&allowedIngredient[]=garlic

or you can get all supported ingredients by querying the metadata:

http://api.yummly.com/v1/api/metadata/ingredient?_app_id=<OUR_ID>&_app_key=<OUR_APP_KEY>

Instacart Data

Processing 37 million rows of shopping data

Downloading and unzipping the Instacart dataset yielded 680MB of CSV data. Here’s the number of lines for each file:

$ wc -l *.csv

135 aisles.csv

22 departments.csv

32434490 order_products__prior.csv

1384618 order_products__train.csv

3421084 orders.csv

49689 products.csv

37290038 total

It looked suspiciously like a database dump. We wanted to query the data to determine how it could be used so we loaded it back into a database.

The first step, convert CSV to SQL. Reading the files directly into our Kotlin app resulted in a significant delay for even the smaller files. When we tried the largest file—bang—java.lang.OutOfMemoryError: Java heap space. In hindsight, stream processing would have been an improvement. However, after speaking to another team who tried this, there was still a long delay reading the entire file in and they eventually abandoned this approach as well.

The second attempt was using Vim; it can load and navigate large files (unlike Excel) but even Vim struggled to perform regex find and replace on these file sizes.

We finally settled on the sed command-line tool. It stands for stream editor and by design avoids loading the whole file into memory by processing each line as a stream.

Let’s take the biggest file, orders_products__prior.csv as an example:

order_id,product_id,add_to_cart_order,reordered

2,33120,1,1

2,28985,2,1

2,9327,3,0

Using tail to remove the header line, sed to substitute the CSV format into SQL and finally a redirection to save to a file, we can write a nifty one-liner:

cat order_products__prior.csv | tail -n +2 | sed 's/.*/insert into order_products_prior values (&);/' > order_products__prior.sql

It took about 30 seconds to execute this command but it’s by far the biggest file (32 million lines) so most of the work is done… or is it?

The most time-consuming part of this task was actually writing the substitution regex for the smaller files. order_products__prior is a join table consisting only of IDs. Other tables involved wrapping quotes around string fields, some of which contained commas themselves (CSVs within one field of a CSV).

product_id,product_name,aisle_id,department_id

1,All-Seasons Salt,104,13

2,Cut Russet Potatoes Steam N' Mash,116,1

3,"Three Cheese Ziti, Marinara with Meatballs",38,1

cat products.csv | tail -n +2 | grep -v "\"" | grep -v "\'" | sed "s/\([0-9]*,\)\([^,]*\)\(,.*\)/insert into product values (\1'\2'\3);/" > products.sql

Having to write group captures in the regex (and escaping the brackets) gets unwieldy fast. OK, so you may have noticed we cheated a little by deleting the lines with annoying quotes.

After writing the regex for each file we had our SQL. We merged the converted CSV files into one big all-tables.sql file.

Now getting it into a database was the next step.

H2 database

Due to the data set size and the time constraints we needed a database that was fast and easy to set up and develop against. We decided to use H2, an in-memory database stored on disk in a single file.

Trying to load the SQL into H2 (via Spring configuration) yielded memory errors again. We solved this by using the split command-line tool:

split -b 100m all-tables.sql

Spot the mistake? We now had a collection of 100MB SQL scripts to import but some scripts were still failing to execute. After fruitlessly hunting for spurious Unicode characters we realised some INSERT statements had been truncated by the split. The fix was to split by line instead of bytes:

split -l 100000 all-tables.sql

Adding primary and foreign key indexes let us join and select from the database tables in near instant time. Sharing the database was then simply a case of copying a single (2.7G) file to each others’ machine with a USB stick. Upon loading the Kotlin application, it would load the database file into memory in negligible time and we had our queryable database available.

Pre-processing the Instacart data set

We did some pre-processing to increase the chances of any ingredients surfaced from the data set matching the list of available Yummly ingredients.

This consisted of adding columns to the product table:

- isFoodDepartment - A join with the

departmentstable allowed for simple pruning of any product that wasn’t part of a ‘food’ department. For example, we ignored the departments, ‘pets’, ‘personal care’ and ‘household’ by setting isFoodDepartment to false. - isIngredientMatch - This would be true if a Yummly ingredient was contained anywhere within the Instacart product name. For example,

‘Chocolate Sandwich Cookies’ contains two Yummly ingredients, ‘Chocolate’ and ‘Cookies’. A naive

String.containsfunction wasn’t sufficient since this is would find ‘cola’ within ‘Chocolate’. Instead, we had to match at the whole word level as well as some basic string fuzzing such as lowercasing and making everything singular instead of plural. The list of matching ingredients for each product was stored in rawMatches.

Apache Mahout recommendation engine

The Instacart data allowed us to mine a single user’s past orders by joining the order table with the product table. This would allow a naive recommendation engine based on that user’s past orders. However, with a little effort, we could use all of the users’ collective data to make richer recommendations.

Apache Mahout provides a framework for implementing performant machine learning ‘applications’; one such application is as a recommendation engine. Mahout contains pre-defined Java classes for constructing a recommendation engine based on historical user interactions. In our case, user interactions were previously purchased product IDs and re-order frequency. It is possible to provide multiple interactions to use as co-occurrence indicators, each with varying weight with regards to the value of the intent. For example, buying a product is a greater indicator of intent than viewing the product. Similarly, ordering a product multiple times shows greater intent than ordering once.

With limited time, we used the most simple implementation with a single interaction of ‘number of times ordered’. We had a recommendation engine with just six lines of code!

This used a UserSimilarity model built by reading in a pre-processed file containing rows for each user, product ID and the number of times ordered. Pearson’s correlation is used to find other users who have a strong positive correlation between their previous purchases and those for whom we require a recommendation. We then use the first five recommended product IDs. As discussed in the previous section, these products were already associated with the Yummly-specific ingredients which could then be fed into a Yummly API query.

This allowed us to find meaningful recipe suggestions for a user, without requiring them to input a specific ingredient or cuisine.

The biggest technical challenge was the required processing of the in-memory database back into a CSV file.

Top Tip - When working with a large dataset, partition batch processing into smaller chunks to avoid losing already processed data when errors occur. Another pitfall was ensuring all rows in the output file were ordered by user ID and contained only contiguous values; a requirement of our chosen Mahout recommender.

Using Twitter as our user interface seemed like a good idea at the time but as you can see from the videos, using Twitter to interact with a chatbot is rather jarring. In hindsight, a Slack, or Facebook bot would have been more user-friendly.

We needed to listen for messages sent to our app and be able to reply.

After the niceness of the Yummly API documentation, the Twitter API documentation was harder to understand (admittedly, the Twitter API is much more complex). It took a while to find a solution in the documentation; we settled on listening for incoming messages via the Twitter Streaming API by using Twitter’s own Hosebird Client.

The base hbc-core module works with the Twitter stream endpoint, handles connection/reconnection for you and puts received messages as raw strings on to a message queue for consumption.

Pulling in the hbc-twitter4j module lets you add Twitter4J listeners and adds a data-model and parser to parse the raw messages into something more manageable.

We generated an access token for our Twitter client, ensuring our token was never committed to Git.

Receiving and sending tweets

For connecting to Twitter and receiving a stream of tweets, we created TwitterIn.kt which connects to Twitter’s streaming API, listens for all messages mentioning us and then passes the messages over to a message listener for processing.

For responding to tweets we created TwitterOut.kt which used Twitter4J to send messages.

Adding images for the recipe

The Twitter API allows you to send a media file as part of a tweet, separate from the rest of the message. To do this we had to:

- Extract the image URL from the Yummly recipe.

- Create a temporary file from the URL, containing the image.

- Add this file to the Twitter message.

- Delete the temporary file.

For more details, click here to see the code.

Update

Since posting the blog, Andy Piper from Twitter suggested using the Direct Message API. We’ve had a look at the documentation and it does look like a better experience for a chatbot. If only our coffee-addled brains had thought of this at the time!

nice read, thanks for the write-up! from a @TwitterAPI perspective, you might also have considered our latest Direct Message APIs with quick replies, buttons, welcome messages etc for a nicer bot experience. https://t.co/aKYc8Aaw36

— andy piper (pipes) (@andypiper) January 10, 2018

NLP with Amazon Lex

We researched a few options around natural language processing:

- Google Cloud Platform’s Cloud Natural Language API looked very full featured but seemed like it would be a bit more work to set up.

- Microsoft Azure’s Luis.ai looked similar and there was a risk that the best documentation would be for .NET and Windows.

- Amazon Lex seemed to have a minimal feature set but looked simpler to get running.

All of these services charge you per-request so the cost would not be an issue for our hack (at $0.00075 per request we wouldn’t be breaking the bank).

Amazon Lex terminology

A ‘bot’ is a service which performs an automated task (‘intent’) on behalf of a user, for example ordering pizza. One intent might have several ‘utterances’ which will trigger it, for example, “I want to order a pizza” or “I’m hungry, give me pizza!” Intents have slots containing properties or parameters for the intent, for example, “large” or “spicy”.

Security in AWS

With an admin user’s AWS credentials, you can spin up AWS instances at will and run up some big bills. There is also the risk of being exploited by malicious people hijacking the processing power for mining cryptocurrencies for example.

The AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM) getting started guide takes you through the basics of creating an admin user.

We wanted an AWS account that only had permission to post text to our ‘Recipe’ bot. We created a ‘RecipeBotRunner’ group that only had the permissions granted by the ‘RecipeBotRunnerPolicy’.

Setting up our bot

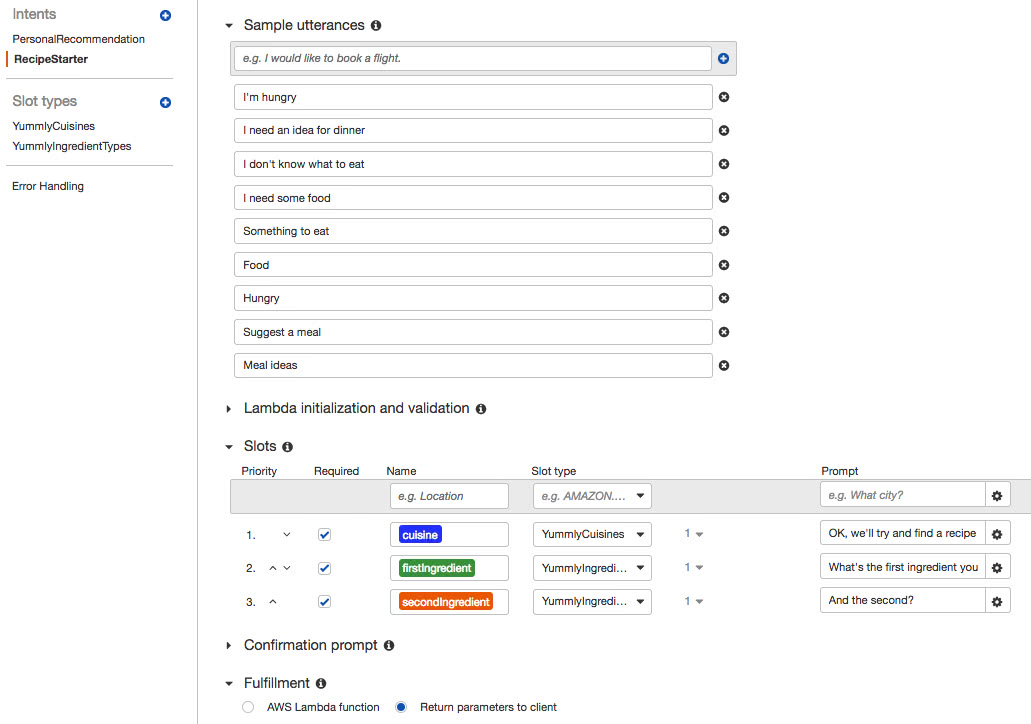

A simple bot for us would have a ‘RecipeStarter’ intent that would be triggered by various utterances. To fulfil the intent required ingredient slots to be populated and included prompts such as, “what ingredients would you like?” Once the user had provided two ingredients, we could send a query to Yummly, get a recipe and tweet it to the user.

Creating a custom Slot Type

For Lex to determine if user data was an ingredient we needed to upload a set of valid ingredients to Lex. Querying the Yummly API metadata for ingredients gave us a list of over 10,000 ingredients. Using the web console to upload these to Lex would take forever so we used command line tools.

The AWS Command Line Interface was easy to install and has great documentation.

Once installed and after running aws configure to set our AWS keys, we could use the ‘PutSlotType’ action

in the lex-models CLI

to create a ‘YummlyIngredientsTypes’ type from the contents of a JSON file.

aws lex-models put-slot-type

--region us-east-1

--name YummlyIngredientTypes

--cli-input-json file://aws-ingredient-slots.json

The format required for the JSON is a set of values, a name + description and a valueSelectionStrategy.

We chose a strategy of TOP_RESOLUTION as we only wanted our bot to accept ingredients that are known to Yummly (by default, any unmatched slot value is accepted as-is).

After creating an ingredient slot type we did the same for cuisines.

Creating an intent to ask for a recipe

Using the AWS console, we created a “RecipeStarter” intent. The intent could be triggered by a number of different utterances and would ask for a cuisine and two ingredients. Once all the slots were filled, the intent was ready for fulfilment.

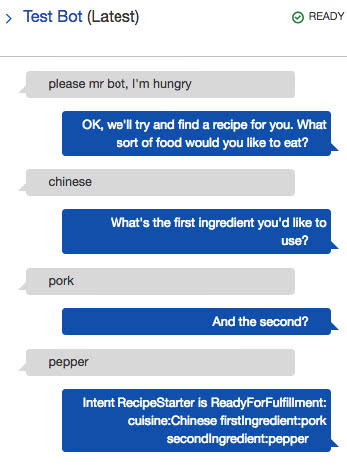

Testing the bot

A bot must be ‘built’ before it can be tested; this is as simple as pressing a build button in the console and waiting for a few seconds.

Once built, the bot can be tested from the console. The screenshot below shows a test where Lex has understood that “please mr bot, I’m hungry” is a match for our intent despite not being an exact match. Lex then prompts the user for the cuisine and ingredient slots. Once the slots are filled, the intent is marked as ready for fulfilment. The fuzzy matching of text for utterances doesn’t apply to custom slot types (as Lex doesn’t know what they mean), but Lex doesn’t care about capitalisation of slot values.

Calling the bot from our app

We imported the aws-java-sdk-lex module from the AWS SDK for Java.

Creating a lex client was then simple:

val builder = AmazonLexRuntimeClientBuilder.standard()

builder.region = "us-east-1"

lexRuntimeAsyncClient: AmazonLexRuntime = builder.build()

The client picks up its AWS credentials from a defined hierarchy. The easiest for us was to start our application with the credentials as environment variables:

AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID=<the key ID for our AWS 'app user'>

AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY=<the secret key>

Sending a user’s tweet to Lex is simple:

fun send(tweetContent: String, userId: String): PostTextResult? {

val request = PostTextRequest()

.withBotName("Recipe")

.withBotAlias("latest")

.withUserId(userId)

.withInputText(tweetContent)

return lexRuntimeAsyncClient?.postText(request)

}

If the returned PostTextResult is ready for fulfilment, the app calls Yummly to get a recipe for the cuisine and ingredients contained in the result; the recipe is then tweeted back to the user. Otherwise, the app sends the message contained in the result as a reply tweet to the user. For example, the message could be a prompt for an ingredient.

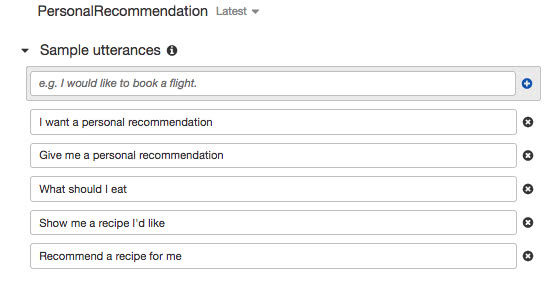

The bot for the data-driven recommendation feature is simply an utterance. No slots are required so it becomes ready for fulfilment immediately.

Enjoyed that? Read some other posts.